Fresh water defines independence at sea. It’s one of those quiet realities of bluewater cruising life that separates weekend sailors from voyagers. Out here, surrounded by an endless horizon of saltwater, every drop we carry—or make—represents safety, comfort, and freedom. On SV Wanderlust, our 2014 Passport 545 Aft Cockpit, water management is not an afterthought. It’s a system, a discipline, and a way of life.

While every boat’s plumbing and tankage differ, the principles are the same. What we’ve refined aboard Wanderlust represents the systems and habits we believe every serious bluewater cruiser should have—reliable, maintainable, and entirely self-contained.

We approach water the same way we approach seamanship: with care, respect, and redundancy. Whether we’re weeks offshore or anchored in a remote atoll, we know exactly where every gallon comes from, how it’s stored, and how it’s used. That knowledge doesn’t just keep us comfortable—it keeps us self-sufficient.

Knowing What’s in the Tanks

We almost never fill our tanks from a dock or shore hose. That surprises people, but it’s deliberate. When you live aboard full time, what goes into your tanks matters. Dock water can contain sediments, chlorine, or bacteria, and many marina supply systems are poorly maintained. Our philosophy is simple: if we don’t know its source, it doesn’t go aboard.

All of our freshwater is produced by our Spectra Cape Horn Extreme watermaker (now sold as the Cape Horn Extreme 330)—essentially a small desalination plant on the aft bulkhead of the engine room. That control gives us confidence. The water is pure, tastes good, and doesn’t risk contaminating our system.

Once a year, typically if we’re in a marina, we “shock” the system with chlorine to sterilize the tanks and plumbing. It’s a quick, preventive measure to make sure any biofilm is eliminated. Beyond that, the system remains closed and clean year-round. After tens of thousands of gallons and many ocean crossings, we’ve never had a single issue with tank contamination.

Over the years, we’ve learned that keeping control over your own water supply pays dividends in reliability. I had the same Cape Horn setup on my previous sailboat, and after nearly two decades of living aboard and making all our own water, we’ve never had a single issue with contamination—or anyone getting sick from the water or food prepared with it. It’s not luck; it’s the result of consistency: clean tanks, disciplined maintenance, and a system we trust completely.

The Infrastructure of Independence

Wanderlust has two stainless-steel freshwater tanks: 95 gallons (360 liters) beneath the starboard settee and 105 gallons (397 liters) beneath the port settee. Together they hold about 200 gallons—plenty for our needs, but not so much that we grow careless. Stainless steel was a design choice we made early on. It’s durable, inert, and doesn’t impart taste the way some plastic tanks do.

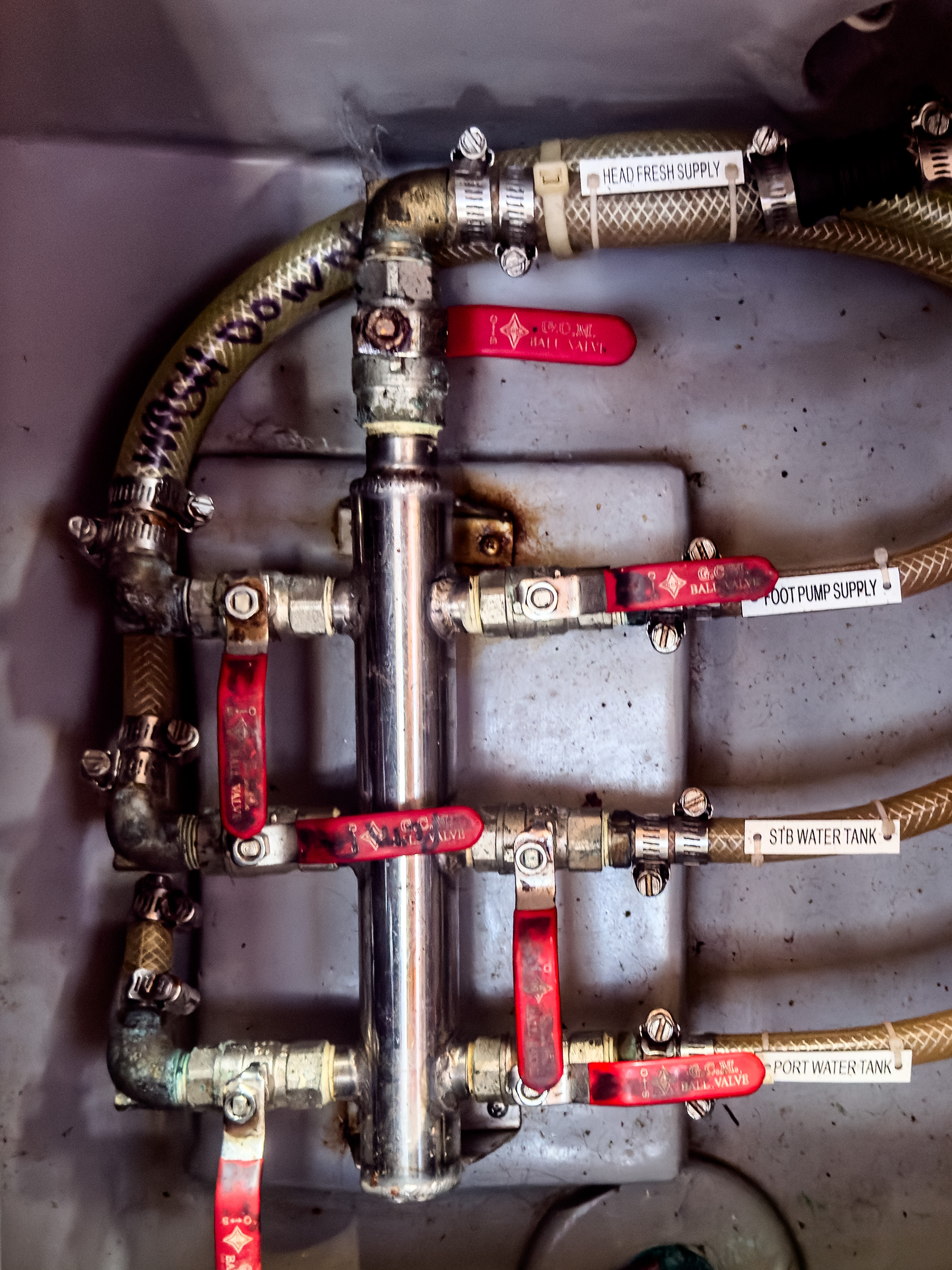

Between the tanks sits a stainless-steel manifold mounted in the bilge beside our 12-volt pressure pump. Through a set of manually operated valves, either tank can gravity-feed the manifold. That means we can isolate one tank if needed, draw down one before the other, or even feed the system entirely by gravity if the pump fails. Simplicity and control are key.

From the manifold, one line runs to the electric pressure pump, another to a manual freshwater foot pump at the galley sink. That foot pump might seem like a relic, but it’s a vital backup. It requires no electricity and makes you think about every ounce you use. Next to it is a saltwater foot pump, equally useful when we’re in clean anchorages.

Our forward head can flush with either fresh or salt water through a dedicated pump system, but we never use freshwater for that purpose—it’s wasteful. All toilet flushes are saltwater only. The freshwater feed exists purely as a redundancy.

The entire system reflects the mindset of a passagemaker: robust, redundant, and easily maintained without a marina in sight.

Life at Anchor — The Comfort of Plenty

At anchor, water use feels almost luxurious—at least by offshore standards—but it still follows a rhythm of discipline. Our Cape Horn isn’t push-button automation; it’s a manual system that requires attention and timing. To keep it healthy, it should be run every three to five days, so we watch the tank gauges and plan accordingly. We’ll typically draw down about two-thirds of one tank, then run the watermaker for a few hours to refill it. It’s not silent—you can hear the steady pulse of the dual electric pumps through the hull—but that sound has become part of life aboard Wanderlust, the hum of self-sufficiency. Those cycles give us enough water for comfort: quick showers, rinsing off snorkeling gear, and even the occasional bucket of laundry in a five-gallon pail—simple, efficient, and perfectly adequate when the tanks are full and the trade winds are steady.

Still, conservation is a habit that never fades. We use “navy showers”—turn the water on to get wet, off to soap up, on again to rinse. Dishes get a saltwater pre-rinse via the foot pump before a quick freshwater finish. Cooking water comes from the sea whenever it’s clean enough, which in remote places like the Tuamotus often means every day.

It makes no sense to desalinate water only to re-salt it for pasta or rice. If the seawater is clear and well offshore of any reef runoff, we’ll fill a pot from the galley’s saltwater pump. Boiling kills any potential contaminants, and the result is indistinguishable from freshwater cooking—except that it costs us nothing.

We also avoid bottled water entirely. Plastic bottles are wasteful, expensive, and environmentally irresponsible. The only bottled water aboard is our emergency supply—sealed rations stored in the ditch bag. For daily drinking, we fill BPA-free Nalgene-style bottles straight from the tap. The watermaker’s output is clean, pure, and far fresher than anything that ever sat in plastic on a store shelf.

With nearly 200 gallons of tank capacity and a reliable watermaker, we’ve never needed to collect rainwater. Still, I keep a set of tarps aboard that could be rigged in an emergency if the Cape Horn ever failed. It’s reassuring to know we could fall back on something as simple as catching rain—but in practice, the watermaker and our storage capacity make that unnecessary.

Life Underway — Efficiency in Motion

At sea, everything changes. Water becomes more precious, and our routines shift to reflect that. Energy priorities move toward navigation, autopilot, and communications, so conservation becomes part of the passage rhythm.

Our safety routine is simple: we minimize water use as much as possible and draw from only one tank at a time. When that tank starts getting low, we switch tanks and immediately run the watermaker to refill the one we just emptied. That way, we always have a full tank in reserve—a safety margin if something goes wrong. The Cape Horn has never failed us, but if it ever did, we’d know exactly how much water we had left to last the remainder of the voyage. Safety first, always.

Long before watermakers were common, sailors like Lin and Larry Pardey managed their water by calculation, not machinery. Lin once described allocating four gallons of water for every hundred miles sailed on their 2,500-mile passage from Mexico to the Marquesas, adjusting their use whenever the number dipped below 2.5. They never ran short. Different tools, same mindset—water discipline has always been the measure of good seamanship.

Showers underway are quick wipe-downs with a damp cloth. Dishes get done mostly with saltwater. We often wash hands and faces in saltwater first, finishing with a short freshwater rinse. Small habits—like turning off the pressure pump between uses—can stretch reserves noticeably.

When the batteries are healthy and conditions calm, we’ll run the Cape Horn underway. In rougher seas, we leave it off; aerated water can harm the high-pressure pump, and it’s not worth the risk. Offshore, it’s all about balance: use what you need, protect what you have.

Running lean doesn’t feel like deprivation. It’s discipline born of experience. After years of passagemaking, we’ve learned that comfort offshore isn’t about abundance—it’s about control and the confidence that comes with it.

The Spectra Cape Horn Xtreme — Turning Ocean into Freshwater

Our Cape Horn watermaker is the quiet hero aboard Wanderlust. It’s a compact reverse-osmosis system that has proven nearly bulletproof through thousands of hours of operation. Rated for roughly 16 gallons per hour using dual 12-volt pumps, it strikes the perfect balance between efficiency and reliability—critical for long-distance sailing where spare parts and service centers are oceans away.

Why the Cape Horn Extreme?

We chose the Cape Horn for several reasons: low electrical consumption, proven reliability in the cruising fleet, and ease of maintenance. Many modern watermakers are fully automated with electronic controls, solenoids, and high-pressure AC pumps that can draw 30 amps or more—and fail when salt air or moisture finds a circuit board. The Cape Horn is the opposite: completely manual, with dual redundant pumps and no electronics to go wrong. If one pump fails, we can still make water—just at a slower rate—with the remaining unit. More importantly, being manual means we decide exactly when to run it and for how long. There’s no unmonitored energy use, no hidden draw on the batteries, just a deliberate, hands-on process that fits the way we manage power aboard Wanderlust. Its Clark Pump energy-recovery system further minimizes power demand, making it ideal for a boat that runs primarily on solar and battery.

Installation and Integration

The unit is mounted on the aft bulkhead of the engine room where it can easily be accessed. The brine discharge exits through a dedicated thru-hull well aft of any intakes. We can isolate every part of the system with valves for service. It’s wired directly to the house bank through a breaker panel, ensuring clean DC power even during heavy inverter loads.

Performance and Operation

Real-world output depends on water temperature and salinity, but we typically make around 16 gallons per hour in tropical waters. We run it every three to five days at anchor, usually mid-morning when solar production peaks. In just a few hours, the tanks are full again.

The Cape Horn is reasonably quiet—more of a low hum than a whine. It’s mounted on the aft bulkhead with vibration-absorbing rubber mounts, and once we close the engine room hatch, the sound fades into the background. You know it’s running, but it’s not intrusive—just another steady rhythm in the life of the boat.

Maintenance Routine

Maintenance is straightforward. A sea strainer sits near the saltwater intake to catch any large debris before it reaches the pumps. Downstream of the pumps—between the electric feed pumps and the Clark Pump/membrane—there’s a 5-micron pre-filter that removes sediment and fine particles. On the freshwater side, a charcoal filter protects the membrane during backflush cycles by removing any residual chlorine. Since we never use dock water, chlorine isn’t a concern, but we still replace the charcoal filter every six months or so. The pre-filter typically lasts four to six months unless we’re operating in dirty water, such as near marinas.

Each time we make water, we let the system run for at least five minutes with product water flowing through the sample tube into the galley sink before diverting it to the tanks. That initial flush clears the membrane and lets us check water quality with a TDS (Total Dissolved Solids) meter. Spectra says anything below 700 ppm is acceptable, but we like to see 400 ppm or less. For perspective, the municipal supply where I once lived in Kanab, Utah measured about 1,500 ppm—typical of “hard” freshwater on land.

Long-Term Reliability of a Sailboat Watermaker

As full-time liveaboards, we never have to pickle the watermaker because it’s used regularly year-round. Over eleven years, I’ve replaced O-rings twice and had one overpressure switch fail—a quick, inexpensive fix. That’s been the extent of the maintenance. For a system that’s as vital as this one, that level of reliability is reassuring.

Fail-Safes and Emergency Preparedness

Despite the Cape Horn’s reliability, redundancy remains central to our philosophy. We keep sealed emergency water rations in the liferaft grab bag. Those rations are never touched unless it’s truly life-or-death.

Our manual foot pump ensures we can still access water if the pressure pump fails or the batteries go down. The bilge manifold’s gravity-feed design means that even with no electrical systems, we can draw from either tank manually. That’s peace of mind you can’t buy.

We’ve also practiced minimal-water living—going days at a time using only what’s absolutely necessary. You learn how little you truly need when you have to account for every cup. That kind of awareness is as valuable as any piece of equipment.

Lessons Any Cruiser Can Apply

- Control your water source — avoid dock fills when possible.

- Keep filtration simple and accessible.

- Run your watermaker regularly to prevent stagnation.

- Build redundancy: manual pumps and gravity feed matter.

- Treat water as both resource and freedom.

Philosophy of Use — Water as a Measure of Freedom

Managing water aboard isn’t about austerity; it’s about awareness. Every system on Wanderlust—from solar to refrigeration to water—exists to support a life untethered from shore. But none demands as much mindfulness as water. You can’t see it being used, but you feel its absence instantly.

In the early years, I tracked every refill, logged consumption, and measured output from the Cape Horn down to the decimal. These days, I still have data—our tank monitor at the nav station constantly shows the level in the active tank, and by habit I glance at it whenever I pass, just as I do with the battery monitor and other gauges. But over time, numbers have blended with intuition. I can usually tell how much water we’re using simply by rhythm and routine, and I’ve learned how quickly new crew can run through it until they adjust to life aboard. Teaching that awareness—how to think about water—is as much a part of seamanship as knowing the sails or the sea.

Our relationship with water mirrors our relationship with the sea: respect it, don’t waste it, and it will sustain you indefinitely. The hum of the Cape Horn, the soft click of the foot pump, the taste of cool freshwater drawn from the ocean itself—these are the quiet luxuries of voyaging life.

Reflections — The Discipline That Becomes Freedom

At anchor, when the tanks are full and the Cape Horn is idle, there’s a quiet reassurance in knowing the system is healthy. We regularly sample the water for TDS, taste, and smell—simple checks that confirm everything is working as it should. I rarely open the inspection plates; there’s no need. The readings tell the story. Those numbers, and the confidence behind them, mean we can stay put as long as we wish, completely independent of shore. That’s freedom measured not in miles, but in self-sufficiency.

For sailors who dream of true self-sufficiency, water is where that dream becomes tangible. Solar gives you power, wind gives you motion, but fresh water gives you life. Managing it well isn’t hardship—it’s the art that makes this life possible.